On top of the bizarre styling, the seller noted the car was an all-electric vehicle built in Englewood. Kavanaugh didn’t hesitate. He had seen his future rotting in a Denver junkyard.

"It has a face only a mother could love," Kavanaugh said. "We just kind of decided: we need to buy one."

Kavanaugh would end up purchasing a different Unique Mobility Electrek that was in better shape than the first vehicle. The film student quickly fell in love with the car's many quirks, including a “defroster” that was nothing more than a Gillette hairdryer attached underneath the dashboard.

Since then, the film student has helped build a community dedicated not only to putting the cars back on Colorado roads but to establishing their place in automotive history.

He set up a website and social media accounts to commemorate the vehicle. Former Unique Mobility engineers even helped Kavanaugh put a pair of the car models back in working order.

"They were Elon Musk before Elon Musk," Kavanaugh said. "Even if not a lot of people know about them, they’re a big reason electric cars are still on the road today."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

A car born from the 1973 energy crisis

Unique Mobility founder John Gould is now 84 years old and lives in Lakewood. On a recent afternoon, he sat down at his kitchen table with binders full of pictures and news articles documenting the company's history. If young grease monkeys have taken an interest in the Electrek, he wants to make sure they get it right.

Gould incorporated Unique Mobility in 1967 with hopes of building a small sports car. To help pay for the project, the business developed a specialty in fiberglass products like kayaks and airplane parts.

Its main focus became dune buggies, which Gould said were often sold to tourist attractions, hobby kits or pizza delivery vehicles.

The company started exploring the possibility of an electric car after the 1973 energy crisis, which left U.S. drivers painfully aware of their dependence on major foreign oil producers. At the same time, Gould started to notice pollution filling the skies above major cities around the world, which he knew was partially due to the rising number of cars.

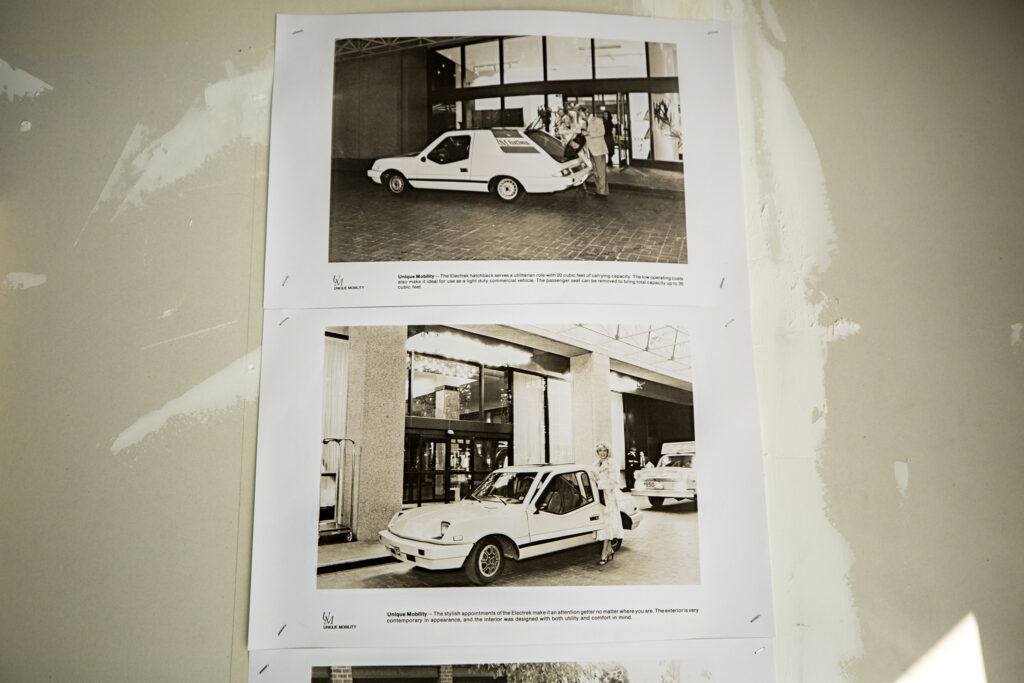

Photo courtesy of John Gould

Photo courtesy of John Gould

"It just seems like the correct thing to do,” Gould said. “If I'm going to be involved in making automobiles, why don't I make something that's kinder to the environment?"

Gould said his company decided to take a "systems approach" to designing a practical battery-powered car. Company engineers and mechanics hung diagrams and lists around their manufacturing facility in Englewood.

Their objective, he said, was to solve problems other auto companies faced in converting traditional internal combustion cars into electric vehicles.

In most cases, those companies piled lead-acid batteries under the hood, which created a dangerous safety hazard. If a driver crashed, Gould said they risked being crushed in a "lead sandwich."

Their proposed solution was a long train of 16 golf cart batteries arranged in a fiberglass tunnel running down the center of the vehicle. The company opted to use fiberglass for the car’s body as well, which an early press release proclaimed was "resistant to corrosion and electric shock."

After five years of development, the first Electrek went on sale in 1979 for $25,000 — about $90,000 today.

Despite the steep sticker price, advertisements promised buyers a car capable of highway speeds and a range of up to 100 miles when driven at a constant speed of 40 miles per hour. The company also claimed the car only cost 1 cent per mile to maintain and operate.

Between 1979 and 1982, Gould said Unique Mobility made more than 50 Electreks.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

The 'Crap Era'

Unique Mobility was not the only company in a rush to build viable electric cars.

After the oil crisis, President Jimmy Carter called for new technologies to soften future oil shocks. A wide range of companies attempted to meet the moment with electric vehicles like the CitiCar, a tiny electric coupe resembling a wedge-shaped Lego piece.

Today's enthusiasts now refer to this period of electric car manufacturing as the Crap Era — a time when automakers lacked the technology or the design sense to create sensible alternatives to internal combustion vehicles.

Kavanaugh said his experience restoring Electreks has shown him the car had some serious deficiencies. After months of rebuilding the car alongside former Unique Mobility engineer Jim McCollough, he was able to take it for an initial spin in 2020. Elated, he recorded a profanity-filled Snapchat for his friends but quickly realized driving the car came with some drawbacks.

One was the car's actual battery capacity. The promised 100-mile range is closer to 50, even with modern golf cart batteries. Rocks and pebbles drum against the car’s all-fiberglass bottom.

Even on a quick trip out of his garage in Monument during the interview for this story Kavanaugh easily got stuck on a slight slope with a layer of snow, proof the 32-horsepower motor doesn’t pack much punch.

All those issues aside, Kavanaugh thinks the Electrek could have been a serviceable car for many environmentally-minded buyers. What he really thinks doomed the car is its looks.

"It is so stupid. You probably saw how stupid it looks driving," Kavanaugh said.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

The Electrek was never made to be aesthetic

Gould isn't offended by the consensus on his electric car’s aesthetics. In fact, he agrees the Electrek "is not a handsome car."

Gould said the car’s look was never a problem because the Electrek was what the automotive industry refers to as a "mule," a short-run production car built to test the reliability and durability of the design.

Many of its quirks — like the drooping guillotine windows and the hairdryer defroster — were necessary to cut back on costs, Gould said.

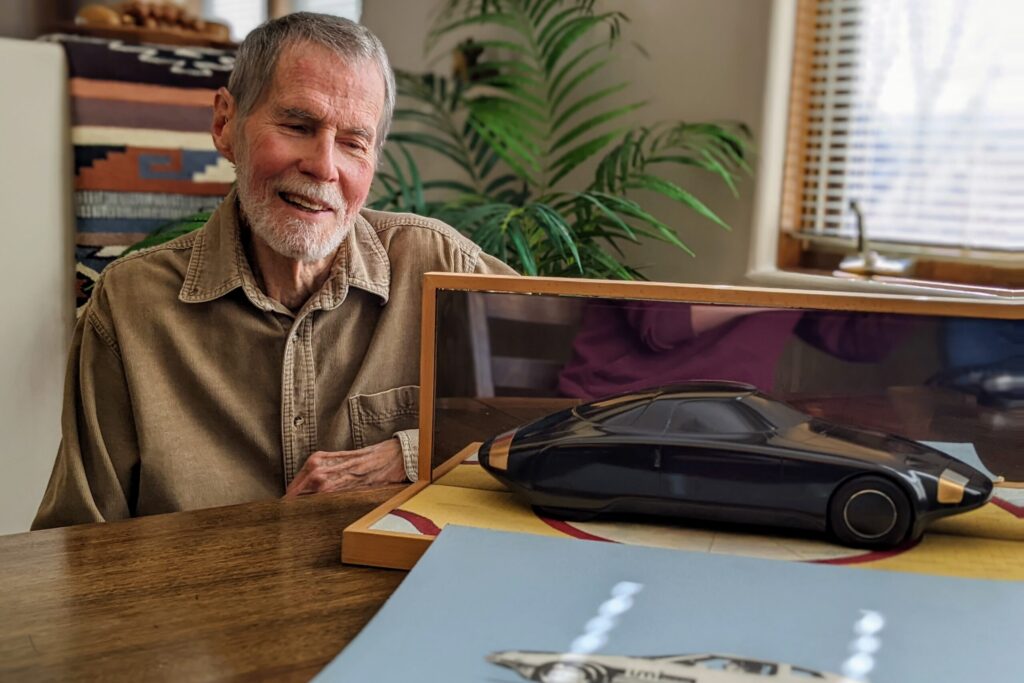

His final vision for an electric car was far more refined. After retreating to a back room at his home, he returned with a sleek, dark figurine of a car model he called the Mariah, named after the country classic "They Called the Wind Mariah."

Sam Brasch/CPR News

Sam Brasch/CPR News

"Our actual preference was going to be this car," he said.

Gould hoped to build the vehicle in Colorado, but he said his company's board of directors decided selling electric car components and expertise was a smarter business move.

After giving up on the Mariah, the company rebranded as UQM Technologies and focused on manufacturing electric drivetrains. Gould said it assisted BMW, Ford and General Motors with electric vehicle research. The work didn’t immediately lead to production vehicles, but he thinks the knowledge is now being applied in new models.

The company also worked with defense contractors and electric vehicle pioneer Chip Yates, who set the record for the fastest climb up Pikes Peak with a motorcycle powered by a UQM motor.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

In 2019, UQM Technologies sold to Dutch conglomerate Danfoss for around $100 million. Despite the success, Gould still thinks about his old dreams of building electric vehicles in Colorado.

"Particularly when I see some of the new electric car companies that are coming on board, they're raising billions of dollars," Gould said. "If I was in my twenties, thirties, forties or whatever, I would probably give it a swing."

As for the young people reviving the old cars, he's perplexed but flattered.

"I'd like to say thanks to them for reviving that old vehicle," Gould said.

He's glad many car hobbyists now agree the Electrek wasn't a dud — it was just ahead of its time.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

"electric" - Google News

May 05, 2022 at 05:01PM

https://ift.tt/bmIdRle

A goofy, Colorado-made electric car is finding a second life with hobbyists - Colorado Public Radio

"electric" - Google News

https://ift.tt/Bpg4moP

https://ift.tt/hYr7xA2

No comments:

Post a Comment